A Book of Verse, a Bag of Apricots and Oscar Wilde

Everyone loves a poem but few people buy collections of poetry. For some the form was killed by school, for others, it can seem lofty and esoteric.

Greetings Readers. Today, as you may have guessed, poetry is the story.

To explain the enigmatic title above I must begin with a personal anecdote. A couple of weeks ago I heard a radio interview with poet John McAuliffe about his new collection, National Theatre.[1] I liked what I heard, and a few days later, when I was in the city centre, bought a copy of the book. I placed it in a bag with some items bought from a health food shop. Having waited for some time on the platform of the DART (suburban rail) station I boarded the train. On disembarking I looked for the bag containing the poetry collection and dried apricots. It was nowhere to be seen. I thought with a pang of the paper bag sitting forlorn on the cold seat of the platform. And yes, I swore too. I had been so looking forward to curling up to read the collection.

The next day being Sunday I figured the lost property office at the station would be closed. I thought it unlikely that anyone else would want the book and the apricots. They didn’t have much resale value either. On Monday I called the station, to be told there was no lost property office but the man on the phone said if the bag had been handed in it would be in his office. After a pause in which I assumed he was looking for it he told me it wasn’t there. Back in town the following week I decided to try the station again. The platform official said there was a lost property office and directed me to it. When I got there the office was empty. I called out ‘Hello, Hello’. No reply. While I waited for someone to appear I glanced around the small bare space until my eyes lit on a poster bearing a poem by Oscar Wilde:

Symphony in Yellow An omnibus across the bridge Crawls like a yellow butterfly, And, here and there a passer-by Shows like a little restless midge. Big barges full of yellow hay Are moored against the shadowy wharf, And, like a yellow silken scarf, The thick fog hangs along the quay. The yellow leaves begin to fade And flutter from the temple elms, And at my feet the pale green Thames Lies like a rod of rippled jade.

New to me, the poem with its strong visual imagery and undertow of melancholy banished my irritation. I left the lost property office thinking that the station master must like poetry too. Perhaps he had kept my book (I wonder what he did with the apricots) but exchange is no robbery. He had given me a poem. The disappearing office was truly a repository of Lost and Found.

Over recent weeks poets have been making the arts news here, with Paul Durcan celebrating his eightieth birthday and Michael Longley publishing a New Selected Poems. Sadly, I missed the reading marking Durcan’s birthday.[2] Last Saturday, however, I was fortunate to see and hear Longley interviewed by former presenter of the Poetry Programme, Olivia O’Leary. At eighty-five, Longley remains intellectually spry and witty, and continues to write poetry. O’Leary guided the conversation around certain favourite poems of his, beginning with one about the jazz pianist, Fats Waller.

Taking his cue from the reference to jazz, a tradition born out of great suffering, he said that poetry needs ‘melody and music, the meaning is in the melody’, and it needs to be memorable. He quoted Edward Thomas’ dictum that ‘a good poem is worn new’ referring to the ‘inexhaustibility’ of a good poem. (As an aside, he said there’s less good poetry about than we might think.)

Those qualities of melody, memorability and inexhaustibility are hard won. Describing the composition of one of his best-known poems, ‘Ceasefire’, he said it began with a couplet describing the image from The Iliad of Priam, King of Troy, embracing Achilles, as he begs the hero to release the body of his son, Hector, for burial. With those final two lines in his mind he figured he could add three quatrains to make a sonnet. ‘It is as cold-hearted as that,’ he said.

Ceasefire 1 Put in mind of his own father and moved to tears Achilles took him by the hand and pushed the old king Gently away, but Priam curled up at his feet and Wept with him until their sadness filled the building. 2 Taking Hector’s corpse into his own hands Achilles Made sure it was washed and, for the old king’s sake, Laid out in uniform, ready for Priam to carry Wrapped like a present home to Troy at daybreak. 3 When they had eaten together, it pleased them both To stare at each other’s beauty as lovers might, Achilles built like a god, Priam good-looking still And full of conversation, who earlier had sighed: 4 I get down on my knees and do what must be done And kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son.

Cold-hearted in its original conception maybe, this sonnet is heart-breaking to read. It was widely read on its publication in the Irish Times because its composition coincided with a ceasefire in Northern Ireland, prelude to the peace process.

Here, Homer’s legendary characters are made contemporary by Longley’s use of familiar phrases ‘moved to tears’ and ‘Taking Hector’s corpse into his own hands’, in a literal and figurative sense, thus, Achilles pushes Priam away, and himself prepares the corpse, with the hand that we learn in the final lines has killed the youth. These intimate gestures and the astonishing images of Hector’s body wrapped like a present, (ironic echo of the Greek ‘gift’ that undid Troy), and of the two men appreciating one another ‘as lovers might’, conjure the complex ambivalence of the relationship between warring opponents. Respecting one another’s strength and ferocity, each nevertheless needs to destroy the other to justify his own motives.

In reaching back to The Iliad, ‘the greatest poem about war and death’, Longley sets his sonnet within a long tradition, deepening the echoes the poem stirs. Likewise, Wilde’s ‘yellow leaves’ chime with the opening lines of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73:

That time of year thou mayst in me behold When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, . . .

To be sure, you don’t need to hear the echo of Shakespeare’s sonnet to enjoy Wilde’s poem but the interplay of poems through years and cultures makes the work more resonant and enhances its fascination. By the same token, while you don’t need to know a sonnet from a sestina to enjoy a poem there is an added pleasure in understanding the basic moves and watching how the poet exploits, varies or juggles them.

Continuing my poetry trail, I have been invited to the launch of the latest collection by Maeve O’Sullivan, titled Where All the Ladders Start a line taken from Yeats’ poem, ‘The Circus Animals’ Desertion’ which ends:

Now that my ladder's gone I must lie down where all the ladders start In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

Best known as a writer and teacher of the Japanese forms haiku and haibun, O’Sullivan mixed these with long-form poems in her last collection, Elsewhere, a journal of a round-the-world trip. This was a deliberate strategy to integrate the two forms and remove haikai from its ‘quasi-ghetto in the wider poetry world’.

This is one of her haibun from Elsewhere:

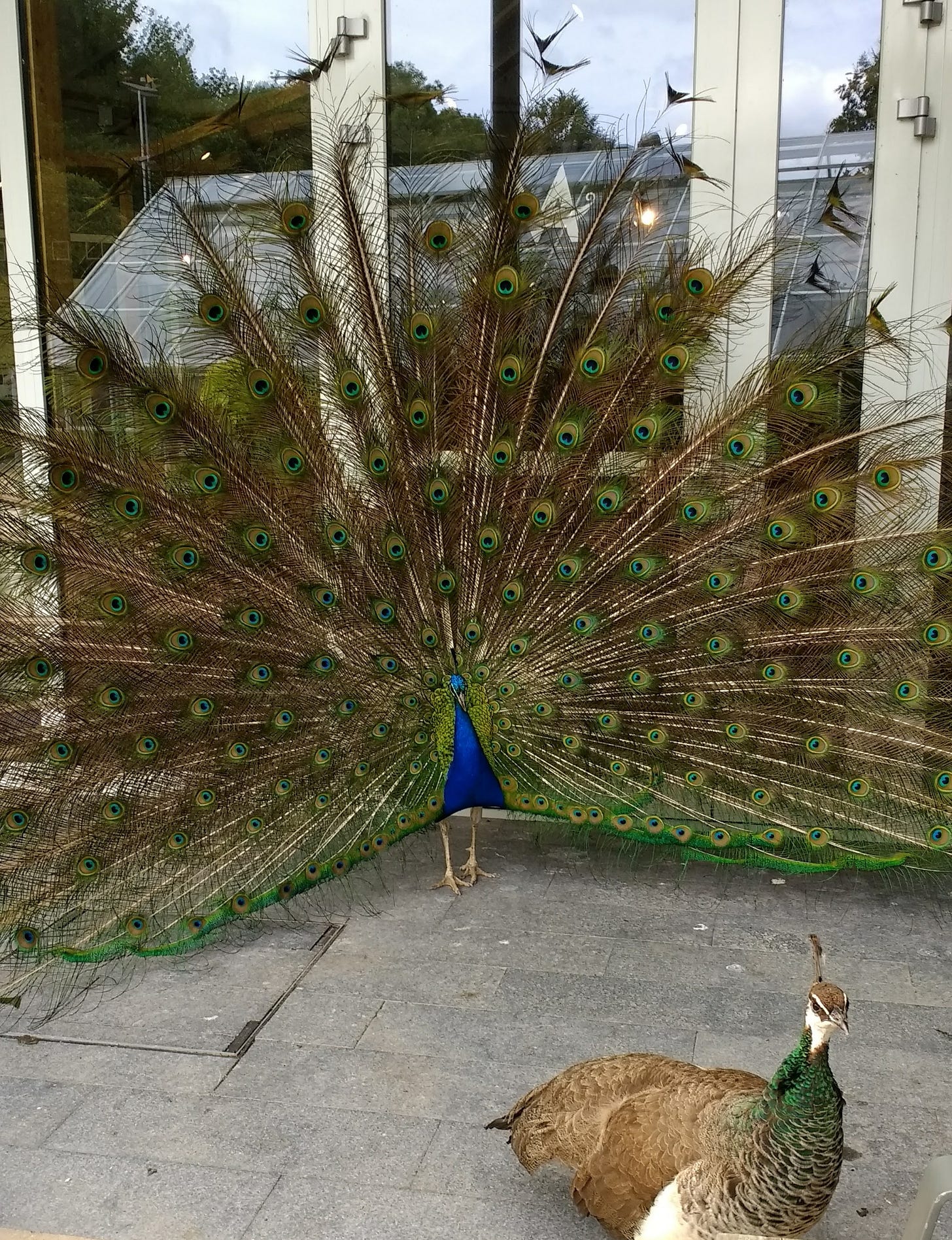

New Delhi new year the peacock struts through a junkyard in trees above the empty swimming pool crows narrow laneway pictures of various gods at pissing level from the tuk tuk between buildings and trees – a flash of full moon

The placing of the words distils impressions from the poet’s journey. The blank spaces may be erasures, such as a painter might make in removing an excess of images, or they may be silence lending emphasis to the words, as the voids on a sculpture. For all their minimalism, the images here are as clear and evocative as those in Wilde’s ‘Symphony of Yellow’. The poet’s art is one of selection, clearing a space around the right word to highlight a detail of sound, colour, gesture, and juxtaposition, balancing images to express a thought or feeling.

A poetry collection is built in the same way, the poems arranged in a pattern such that they echo and refract one another across the pages. Read through from beginning to end, a collection brings us on an adventure through the poet’s imagination, offering us new angles of vision on the world. Each poem can be enjoyed in its own right, and within that whole and each time we re-read a good poem we find new riches there, thanks to its ‘inexhaustibility’.

While many people reach for a poem in times of stress, anxiety or grief, the discovery of a poem at any time, on any day, can refresh, inspire or intrigue us. A book of poetry is a great companion, especially when you’re waiting for a train. That was my mistake – not to take National Theatre out of the paper bag and read it while sitting on the platform. But then I wouldn’t have found Wilde’s ‘Symphony in Yellow’ and I would have been the poorer.

[1] https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22448270/

[2] Paul Durcan’s poetry is best appreciated by listening to him read, in his distinctive soft, plangent voice and dead pan delivery. Interview with Paul Durcan; and a reading in 2016 Paul Durcan reading

Whether you’re a poet, poetry lover or occasional reader of poetry do share your thoughts here:

Thank you Christine. I think sometimes the classics, like the Iliad are spoiled for people by being forced on them at too early an age. It can be offputting, which is a shame because there are such riches there.

Thank you, glad you enjoyed the poems and the essay.