Magic windows and the eye of the imagination

'More than glass', to quote Louis MacNeice, a window is a miracle in its own right, as understood by poets and artists of many generations

Greetings from France! After travelling for ten days through Reims, Strasbourg and Dijon, I realise that most of the photos I’ve taken are of windows, from glorious stained glass in Reims Cathedral to the ornate windows of old buildings in Strasbourg and reflections in sheets of smoked modern glass in Dijon.

That led me to reflecting on the windows we live with, write about and paint. Starting with the software I’m using to type this essay, and the good reason it is so named because it opens new virtual horizons to us, one after another receding to infinity like nested Chinese boxes until we lose sight of ourselves altogether.

At my first undergraduate lecture in Old English, our professor, Alan J. Bliss, spoke of the world in which the early texts we would study were written, and somehow came around to calling on us to imagine the difference the invention of glass windows made to their authors, allowing daylight stream in no matter the weather. I was enchanted, not just by the concept (forgive my naïve suburban teenage self!) but by the picture that filled my mind, as clear today as then, of stern monastery walls disrupted by a panel giving access to a vista of blue.

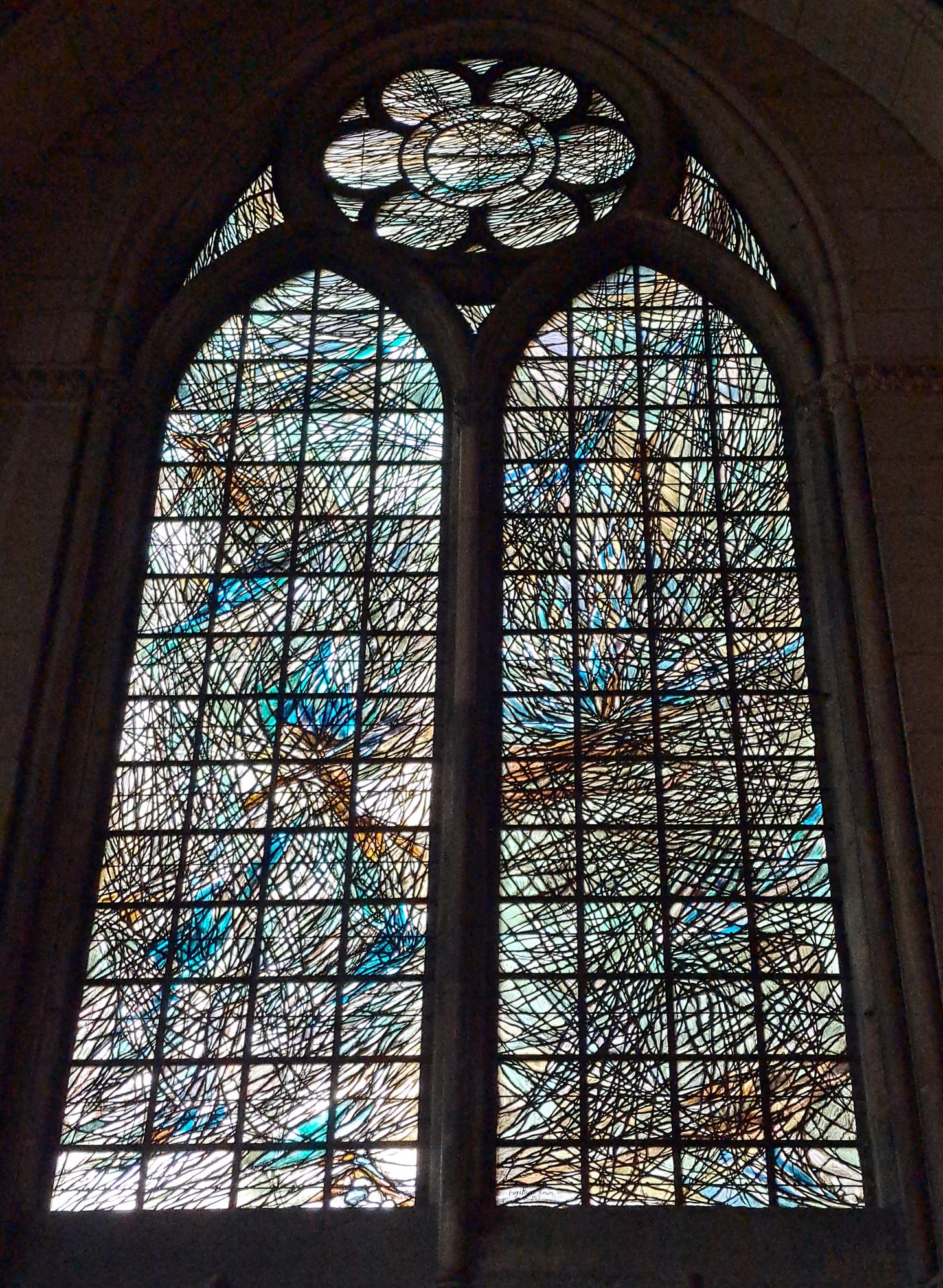

Last week I chanced upon the same blue in Marc Chagall’s windows for Reims cathedral, a shade favoured by medieval artists and recreated by the artisans of the centuries old Simon glassmaking workshop. Nearby is a grisaille window entitled ‘The Waters of Life’, made by a scion of the glassmaking family, Brigitte Simon-Marq, where light swarms across the glass in dashes and flecks of colour.

Having discovered the brilliance of glass as a medium of illumination, artists discovered that staining it transformed the window from light source to celebration of light, dismantling and rearranging its spectrum to tell stories and inspire wonder.

Is it any wonder that today we decorate our windows for autumn and winter festivals using candles and coloured lights to compensate for the short days? Long ago there was a poignant tradition in Ireland of keeping a candle lit in a window to welcome the returning emigrant, who rarely did come home. Most figurative uses of the word ‘window’ are positive, we have a window of opportunity, or when we are broke we window shop, dreaming of wearing that shirt, driving that car, rattling that jewellery. Window dressing may be shallow but at least it’s pleasing to the eye.

The romance of windows is clear too in their literary manifestations. And I’m not only talking about Romeo’s famous lines:

But, soft! What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east and Juliet is the sun. (W. Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet II: ii)

Here the ‘window’ is reversed as Romeo, looking in, sees the sunlight that should by rights be outside. This inside-out effect, and his reordering of the compass, accentuates the agony he suffers at loving her against his conscience and family loyalty.

While the windows give us light to read and see by the eyes can also be seen as windows, in Shakespeare’s wordplay. Here is his Sonnet XXIV:

Mine eye hath played the painter and hath stelled Thy beauty’s form in table of my heart; My body is the frame wherein ’tis held, And perspective it is best painter’s art. For through the painter must you see his skill To find where your true image pictured lies, Which in my bosom’s shop is hanging still, That hath his windows glazèd with thine eyes. Now see what good turns eyes for eyes have done: Mine eyes have drawn thy shape, and thine for me Are windows to my breast, wherethrough the sun Delights to peep, to gaze therein on thee. Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art: They draw but what they see, know not the heart.

Well that’s one way of describing new lovers’ endless gazing into one another’s eyes. But Shakespeare draws out the possibilities of his metaphor with classic wordplay, the eyes are windows which here become mirrors – look at all the doubled words – as the lover seeks her/his reflection in the speaker’s eyes and the speaker in turn sees his image/painting of the lover reflected back at him in the lover’s eyes, all of which is a teasing surface impression that yet masks the heart’s secrets.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning deploys this image too in her long poem ‘Aurora Leigh’, a portrait of a woman much like herself eager to break the confines of Victorian domesticity, she nurtures her intellect with books.

But I could not hide My quickening inner life from those at watch. They saw a light at a window now and then, They had not set there. . . . (from 'Aurora Leigh' I)

Ironically, Barrett Browning’s compromised health kept her indoors for much of her life and relieved her of domestic duties, thus freeing her to read and write. Prior to ‘Aurora Leigh’ she had written the dramatic ‘Casa Guidi Windows’, her observation of the Italian Risorgimento from the windows of her home in Florence.

Much like a livestream, she shares breaking news of the accession of Duke Leopold of Tuscany:

And all the people shouted in the sun. And all the thousand windows which had cast A ripple of silks, in blue and scarlet, down. As if the houses overflowed at last. Seemed to grow larger with fair heads and eyes. (from 'The Casa Guidi Windows' (xiii) )

These ‘windows’ also open back to the history of Italian politics, religion and literature which have led to this moment, and its disappointing aftermath.

Freedom of a more personal nature features in Oscar Wilde’s harrowing account of incarceration in ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’. Excoriating the figure of those who are guilty but free he writes, ‘He does not stare upon the air/ Through a little roof of glass:’. Air more than light is the tonic the prisoner craves in his foetid cell, the narrow window his only glimpse of freedom.

A window is a many-faceted thing for the creative eye, its transparency an illusion because it also mediates the world, framing what we see, a trick conjured in Louis MacNeice’s famous ‘Snow’:

The room was suddenly rich and the great bay-window was Spawning snow and pink roses against it Soundlessly collateral and incompatible: World is suddener than we fancy it. World is crazier and more of it than we think, Incorrigibly plural. I peel and portion A tangerine and spit the pips and feel The drunkenness of things being various. And the fire flames with a bubbling sound for world Is more spiteful and gay than one supposes— On the tongue on the eyes on the ears in the palms of one's hands— There is more than glass between the snow and the huge roses.

Tripled and thickened nowadays, the better to insulate us while we work or browse on our screens, glass yet gives us ownership of a view. The Icelandic author, Audur Ava Olafsdottir, suggests this, when describing her writing cabin outside Reykjavik: ‘From my windows I see five volcanoes.’[i] Woolf’s ‘room of one’s own’ becomes a room with a spectacular view, which, far from being distracting, aids the concentration, providing a resting place for the eyes from the screen/page and a breathing space for the imagination.

Even the downbeat Philip Larkin cannot resist the inspiration of windows, his ‘Whitsun Weddings’ a marvel observed from train windows, which symbolise his detachment from such uninhibited joy. And, starting from voyeurism in ‘High Windows’ he proceeds to awe:

. . . And immediately Rather than words comes the thought of high windows: The sun-comprehending glass, And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless. (from ‘High Windows’)

Miraculous, indeed, the invention of glass, its practical efficiency magnified by its metaphorical potential.

[i] Le Point 4 September 2025, p. 80.

Thank you for joining me today. It’s been a while, I know but this is to say I haven’t forgotten my readers! Please share your thoughts, ideas and quotes on windows here.

Great piece Aisling, very interesting and informative plus gorgeous photos. Enjoy your travels!

Love your words and your photos Ash😍