Reputation and the Right Reader

In which Elizabeth Gaskell goes toe to toe with George Eliot

Am I alone in coming late to the work of Elizabeth Gaskell, or in reading her at all? If so, why is that the case when the work of her friends Charlotte Bronte and Charles Dickens, is ever popular and regularly adapted to the screen and stage? Likewise, her near contemporary, George Eliot, continues to be well regarded and widely read.

Unlike these writers, Gaskell focuses almost exclusively on female sensibility, the situation of women in nineteenth century England and the effects of the industrial revolution on the working class. She also treats of faith but without preaching or dogma. Her husband was a Unitarian minister who encouraged her to write as a distraction from the death of her infant son

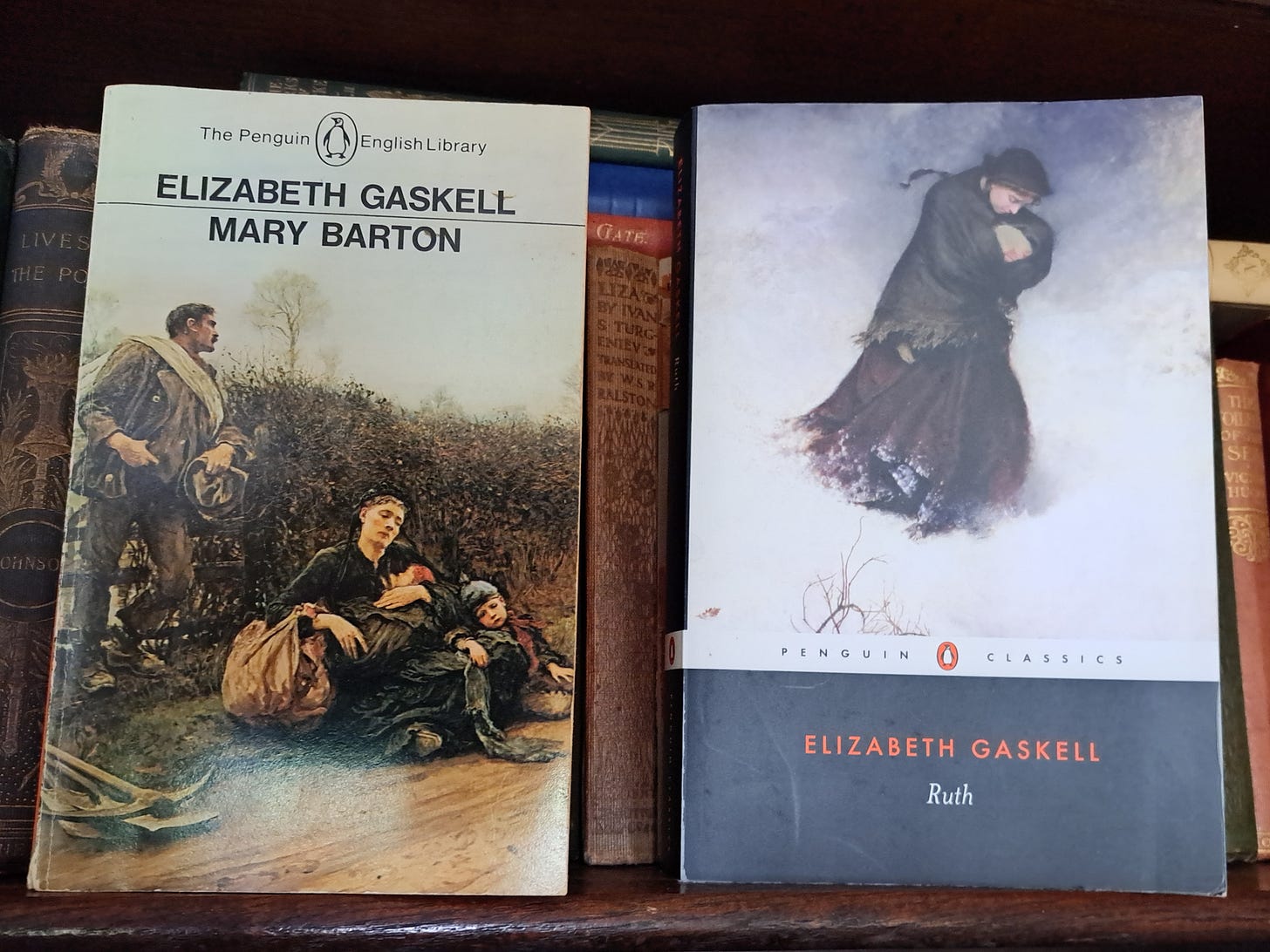

For some reason, maybe because a teacher had mentioned Gaskell, I bought her first novel, Mary Barton, in my final year at university. Unread, the book accompanied me through countless dislocations and relocations, until three years ago. Then, after enjoying a BBC dramatization of North and South, I rescued Mary Barton from her place on the shelf between Dickens and Eliot.

Reader, I loved it! Mary is a young woman of quiet passion and courage who acts to save her beloved from a miscarriage of justice, even though that means condemning her father. Gaskell brings us into the homes, lives and deaths, of a working class community and the early Chartist (trade union) movement is integral to the central love story, without being polemic.

Last year I chanced on another Gaskell novel, Ruth, which also features a strong, intelligent heroine. Ruth is an orphan seamstress whose naïve belief in the innate goodness of natural feelings leads her to live openly with a man although unwed, a strict taboo in Victorian society. Left alone, Ruth, now pregnant, is taken in by a Dissenting preacher and his sister who compromise their principles with the lie that she is a widow. Far from being pious and worthy, however, the novel dramatizes a moral conflict, brutally heightened when the truth of Ruth’s position is revealed. Yet, despite the pain of being shunned and shamed she cannot erase her love for Mr. Bellingham. The scene of their later meeting gripped me with dread of what she might do.

As I read Ruth’s story I recalled Eliot’s Adam Bede which tells a broadly similar story but with a very different outcome. Even the title, like so many of Eliot’s, emphasises the male protagonist (Silas Marner, Daniel Deronda). Bede is a bit of a bore and Hetty is a spoilt child whose delusions lead to her seduction and pregnancy. She kills her baby and is deported to Australia. It is a shocking tale but the narrative foregrounds the actions of the men and not the suffering conscience of the woman.

By contrast, the account of Ruth’s anguish is heart-wrenching. Twice she contemplates suicide rather than taint her child with the shame of her situation but each time the thought of that child recalls her to life and she commits herself to raising him well. While belief in God is important to her the novel is not one of religious conversion or unquestioning adherence to doctrine. The faith on which she relies is alive in the natural world, a felt presence more than a revealed truth.

Ruth is a novel about women, from Ruth’s harsh employer, Mrs. Mason, to the initially grumbling but eventually welcoming housekeeper, Sally, and young Jemima Bradshaw, who stands up to her father and defends Ruth. The men take second place to these women and Ruth is always centre stage. Gaskell’s women have more spine and character than most of Eliot’s who, after all, are presented through the filter of her putative masculine narrator and whose lives are determined by their relationships with men. For all that I admire Middlemarch and have read it at least three times I can’t help being disappointed that Dorothea ends by marrying Ladislaw and I can’t for the life of me understand Gwendolen’s obsession with Daniel Deronda.

In her lifestyle Eliot (or Mary Ann Evans) flouted Victorian mores by living with a married man, whose name, George, she adopted as her pen name. Gaskell, on the surface more conventional, uses her married name, but never assumed a male persona in her writing. Her work is chiefly preoccupied with the situation and moral growth of working class women. Eliot’s women, for the most part, are middle class dreamers. Some years ago, listening to an Audible recording of Middlemarch I realised that the lifeblood of the novel is money. Needing, getting, spending, stealing and bequeathing it is what connects the characters to one another. In Gaskell’s Ruth and Mary Barton love, in all its manifestations, maternal, sibling, kinship and friendship, is the common currency.

Here is Ruth watching her son:

“It was beautiful to see the intuition by which she divined what was passing in every fold of her child’s heart, so as to be always ready with the right words to soothe or to strengthen him.”

The heart’s truth that Ruth had followed in her youth is deepened by the end of the novel when, during a typhus epidemic, she comforts those in the throes of ultimate pain. As an aside, Gaskell’s description of the disease and the fear it struck in people’s hearts could have been written two years ago when the world was in the grip of Covid-19.

I wonder, however, would Mrs. Gaskell have inspired me with the same zealous enthusiasm had I read Mary Barton all those years ago. Maybe these novels have come to me at a time when I am, not wiser, but more willing to accept that there are many things I do not know or understand, most of them in the human heart.

Could it be that books choose us, rather than the other way around? What do you think? Do share your thoughts on books that have surprised you.

Absolutely right, Rhona! It was well worthwhile keeping it, still with the original price sticker! Gaskell certainly merits our attention. I'll be hunting up some more of her work now.

Interesting that you get to read this now. If you kept the book that long you were destined to read it. Glad that it was worth keeping!