Shakespeare, Dickens and the ‘Great’ Chestnut

How great is these writers' art and why does greatness matter?

Hello Readers,

Here’s a perennial controversy to gnaw over: what constitutes ‘greatness’ and where does the epithet get us in respect of our respect for writers? I thought we had moved on from the adulation for ‘dead white male’ writers but I was either mistaken or just plain naïve.

In yesterday’s Observer newspaper (Sunday 2 March 2025) three pages of ‘The New Review’ supplement are devoted to a discussion of the relative greatness of Shakespeare and Dickens. The main feature is by former Oxford don, Peter Conrad, who has published a book entitled Dickens the Enchanter: Inside the Explosive Imagination of the Great Storyteller (Bloomsbury Continuum). In a side bar the editor of the page has asked ‘prominent writers’ (ie those who are not yet ‘great’) to vote on ‘Who’s better?’.

Conrad ascribes royal status to the two writers, pondering which has ‘supremacy’, whose work is ‘sacrosanct’ or which deserves to occupy a throne, all bound up with their expressions of patriotism. Of the ‘prominent’ writers consulted, Nigerian novelist, Chibundu Onuzo, is the most astute, saying, ‘I roll my eyes when I hear someone arguing that a certain author challenges Shakespeare’s “crown”. It’s very British, very Eurocentric. . . . it’s not a competition.’ Precisely.

As part of his argument for Dickens’ superiority Conrad cites a character in Martin Chuzzlewit who objected that Shakespeare’s heroines ‘have no legs at all’, adding that his characters have ‘minds and voices, but otherwise they are bodiless, needing actors to supply them with faces and physiques’. Er . . . yes, Peter, they’re plays.

Jamaican-Caymanian writer, Sara Collins, rightly says that comparing a playwright with a novelist is ‘a bit like comparing an apple with an orange’. Elif Shafak wants the two boys to move over on the throne and make room for Virginia Woolf, who famously posited the situation of Shakespeare’s putative sister, Judith, in A Room of One’s Own.

This female Shakespeare would not have received the same education as her brother with the result that ‘To have lived a free life in London in the sixteenth century would have meant for a woman who was poet and playwright a nervous stress and dilemma which might well have killed her.’ Although she had the freedom to write, Woolf’s gender prevented her attending university. Instead, she had to content herself with discussing Shakespeare and other literary matters with her brother Thoby who went up to Cambridge.

This ‘sister’ turns up in the title of a Smiths’ song where she also refers to Laura Wingfield in Tennessee Williams’ play The Glass Menagerie. Her brother Tom is nicknamed Shakespeare because he writes poetry during breaks in his warehouse job. So here Shakespeare meets Woolf, Williams and Morrissey, who wrote the song’s lyrics.

I thought that if you had An acoustic guitar Then it meant that you were A Protest Singer Oh I can smile about it now But at the time it was terrible No, Mamma, let me go

This confluence reflects the extent to which the Bard of Avon is inscribed in our cultural DNA. The playwright and poet who drew on history, folktale and myth for his work has himself become a myth, a status enhanced by the paucity of his biographical detail.

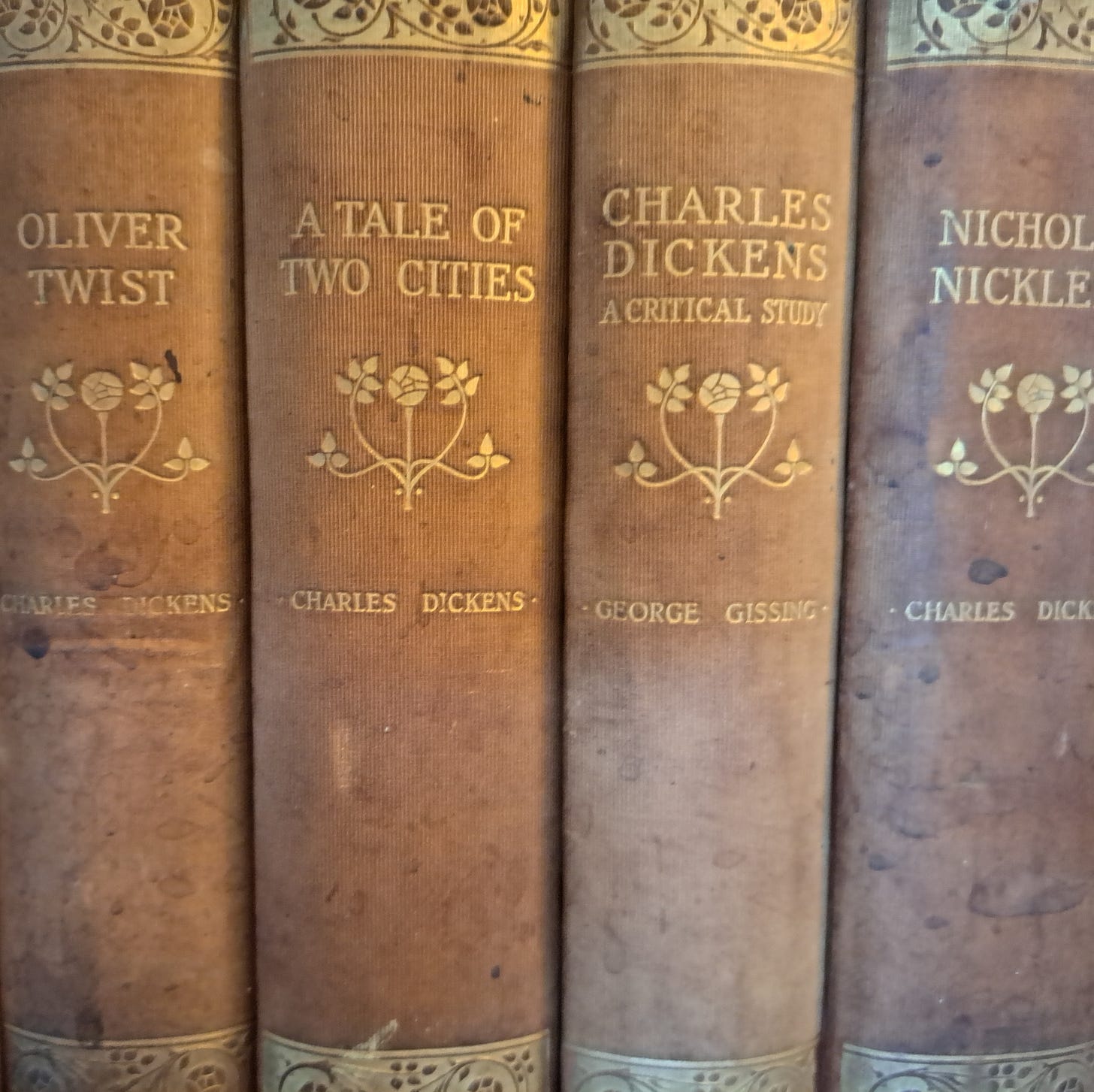

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy Shakespeare’s and Dickens’ work as much as many another. A teacher on my BA English course told us Shakespeare’s complete works were essential reading, advice I followed gladly. A different teacher thought it sufficient to play Cleo Laine singing ‘Shakespeare The Compleat Works’. Later, I took to reading a Dickens novel every winter. I love my collection of his books that I admired as a child in my grandparents’ home.

This morning I asked a playwright friend what she thought of Shakespeare. ‘Not a fan,’ she said. ‘He’s not relevant today, unless someone does something completely new with one of the plays. If I wanted an evening’s entertainment I wouldn’t say let’s go to see Othello.’ She did, however, find studying his work rewarding but prefers to read Dickens.

So what is this concept of ‘greatness’? How can one writer hold sway over all others? Had Shakespeare had not existed would we have had to invent him? Ditto Dickens? Maybe we would have read other authors and arrived exactly where we are now. If Woolf’s invention, Judith Shakespeare, had lived, been educated and written women might have been, and continue to be, wiser, better, and happier. Woolf’s essay is an excoriating condemnation of the oppression of women, and much of her writing aimed to express the silenced female consciousness.

The character of the shell-shocked Septimus Smith in her novel Mrs. Dalloway ‘went to France to save an England which consisted almost entirely of Shakespeare’s plays and Miss Isabel Pole in a green dress walking in a square.’ Here we are again, connecting the bard and patriotism. Miss Pole had taught Septimus about Antony and Cleopatra but did not reciprocate his feelings for her. After fighting in the trenches he finds only misanthropy in Shakespeare’s poetry.

Is that the measure of greatness the extent to which a writer’s words are quoted in everyday parlance? Or have we been conditioned to reach for certain phrases because their authors have been prescribed as upholding certain principles, best formulated in their words? When I was a parliamentary reporter (like Dickens, although he worked for a newspaper, I for the Official Report) I heard Mr. Micawber’s advice to David Copperfield regularly quoted, to no effect, on Budget Day:

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds nought and six, result misery.

Legal debates were often peppered with references to Jarndyce -v- Jarndyce, the interminable dispute over a will in Bleak House. The word ‘Dickensian’ was used to conjure poverty and dilapidation, although Dickens’ heroes and, rare, heroines, are invariably rescued and raised to the middle class. Capitalism is the grand narrative here, as monarchy is in Shakespeare’s plays. Hence the presence of these works for so long on educational curricula in the Anglophone world.

Woolf had it right when she wrote, reviewing a book by the unfortunately named W. Walter Crotch (even Dickens didn’t come up with that one!), The Secret Dickens, ‘Perhaps no one has suffered more than Dickens from the enthusiasm of his admirers, by which he has been made to appear not so much a great writer as an intolerable institution.’ There’s that word again. Although Woolf was not a fan of the older novelist she did admire David Copperfield and Bleak House. She goes on to compare him to Shakespeare:

Like Shakespeare and like Scott, his faults are so colossal that, had he been guilty of them alone, one might have inferred the prodigious nature of his merits. The extravagance of a first acquaintance wears away; doubts and difficulties arise; the book marker stays wedged in the mass of Nicholas Nickleby for months at a time; the Brothers Cheeryble prove almost insurmountable; and yet the certainty is none the less sure that somehow or other Dickens was a very great man.

Even Woolf cannot get away from that word, which continues to bedevil our culture. It seems we must be always on the look out for greatness for without it a writer, artist, sports star or public figure is nothing. To say nothing of countries. Could we be said to live in an era of toxic greatness? The epithet does not serve its subject nor the public. Writers and artists need to be appreciated on their own terms and in their own contexts, not enlisted into a pantheon to be worshipped and later perhaps vilified when it emerges that they were as fallible and frail as the rest of us.

Let’s please read Dickens’ novels, watch Shakespeare’s plays and read his poetry for pleasure and insight into the human condition, but not for moral improvement or edification. Their work is not the gold standard by which others should be judged, it is sufficient unto itself and remains true to their vision alone, which should be more than enough for us too.

So how would you respond to the question ‘Who’s better Shakespeare or Dickens’?

Thanks. It is refreshing to see these ”greats” in perspective of their own time and place. It actually makes it easier to appreciate their work than when they were presented, in school, as near deitie who coincidentally represent the greatness of the anglophone world.

Exactly. It carries the whiff of colonialism and empire which is not to say the works of these writers cannot be enjoyed outside the anglophone world but on their own terms only!