The Dying Art of the Letter

Has digital communication rendered a classic fictional form obsolete?

Last week I received a letter, personal and handwritten. I read it three times, not just for the kind sentiments expressed there but also for the warmth of personality in the handwriting, two hands, his and hers. It is so rare these days to receive such a letter that I enjoyed the palpable sense of contact it brought. Meanwhile, I’m reading Delphine (1802) by Madame de Staël, a novel narrated in an exchange of letters, chiefly between two women, about money and men, in that order.

That coincidence raised the question, whither the epistolary novel in the age of electronic communication? Don’t get me wrong: as you can see, I’m a big fan of contemporary technology, and I thoroughly enjoyed Matt Beaumont’s novel E. written as an exchange of emails. But letters have a tangible duration that email, text and tweet/X messages lack.

Library shelves are filled with volumes of writers’ letters, The Letters of Seamus Heaney, edited by Christopher Reid, being one of the latest additions to the collection. Maybe also one of the last. In their youth Heaney and his poet friends liked to exchange poem-letters and one, Derek Mahon, published a long poem entitled The Hudson Letter (1994), written during a stay in New York. We are fortunate to have these living testaments to the lives of the poets. Email is a more ephemeral exchange and unlikely to be preserved.

Lost letters were a popular trope in nineteenth century fiction. Think how different Tess of the D’Urberville’s life would have been had she received Angel Clare’s letter in Hardy’s novel. In those days, in the cities at least, letters were delivered four times a day, making them almost as speedy as our emails. The fictional trope therefore had a basis in real life.

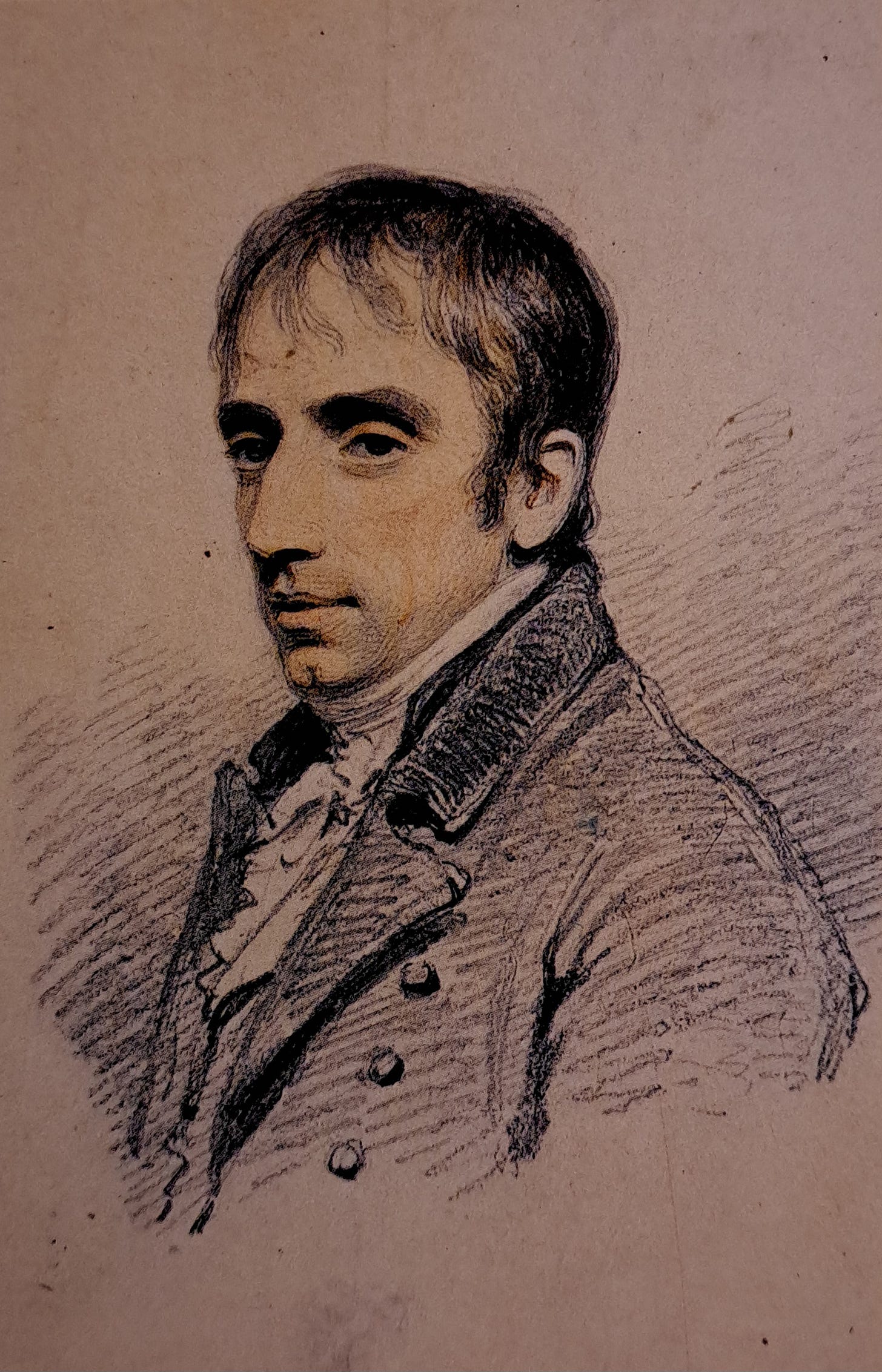

Today we can read heart-breaking letters from Wordsworth’s French lover and the mother of his first child, Annete Vallon, which were found in a police sub-station in France 125 years after being written. They had never reached the poet in England because the two countries were at war. The love letters between him and his wife, Mary Hutchinson, were found in 1977 in a heap of scrap paper. Part of their interest is that Mary, having kept the letters, years later annotated the one informing her of her four-year old daughter Dora’s death. She was appalled to realise that this had happened while she had been away enjoying herself. Thus the letters acquire another layer of meaning as touchstones of memory and conscience.

Although there are overlaps between a letter and an email, each remains quite distinct from the other. Like a journal, the letter can be intimate but where the journal is (usually) intended only for the writer’s eyes, the letter is tailored to the recipient. The email can be intimate and tailored to the recipient but we all know that it can be read by many eyes and information pulled from it to build an algorithmic profile of our likes and dislikes for marketing and other purposes.

Add to this the fact that the software often supplies words and phrases to save us typing and we resort to acronyms for speedier communication, FYI and BTW, ICMYI, IMHO, BW, among others. This technological jargon and assistance can render an email anodyne or even a tad impersonal. There is also the difference between the mechanical act of typing, or using your thumbs, and the calligraphic pleasure of handwriting. (Whither, too, the graphologists today?)

Like many an Eng Lit undergraduate I was made to suffer through Samuel Richardson’s two volume epistolary novel, Pamela or Virtue Rewarded (1740-1). Perhaps our teacher at the time lacked imagination because nothing of the scandalous subtext was mentioned in class. Instead, the novel was prescribed as some kind of moral chastener, essential to an understanding of the development of the novel form. Much more entertaining was Fanny Burney’s Evelina, (1778) because the letter-writing heroine has a witty take on London society. Classic epistolary novels include Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774, 1787) and Shusaku Endo’s very moving novel, Silence (1966):

Today, while writing this letter, I sometimes go out of our hut to look down at the sea, the grave of these two Japanese peasants, who believed our word. The sea only stretches out endlessly, melancholy and dark, while below the grey clouds there is not the shadow of an island.

More recently, Alice Walker’s Pulitzer prize-winning novel, The Color Purple (1982) is presented as a series of letters between women, while Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead (2005) (also a Pulitzer winner) takes the form of a long letter from father to son. Sally Rooney uses an exchange of emails between the two women at the centre of Beautiful World Where Are You? (2022) to reveal their emotional lives, re-working the trope from the earlier tradition for a modern audience. In this case, however, the exchange is bookended by third-person narratives.

The letter as a narrative device has several facets and purposes. In the early examples such as Madame de Staël’s and Richardson’s the author plays on the irony of the dissimulation practiced by the letter writers. Delphine and her sister-in-law, Louise, gossip about and criticise Delphine’s relative, the formidable Madame de Vernon while manipulating a marriage for her daughter.

Their exchanges highlight the constraints imposed on women in revolutionary France. Correspondence affords them a chance to express their views and discuss their particular situations in confidence and without fear of censure. Occasional letters from the love object Leonce, show him to be an awful prig, making us wonder how the intelligent and independent Delphine can fall for him, sight unseen.

Here, as in Richardson’s and Burney’s novels, the interest is as much, or even more so, in the unsaid as the said. The first-person narratives provided by the letters allow for more subtlety than the conventional, omniscient third-person narrative. In a time when letters shuttled back and forth, this was a plausibly ‘realistic’ device. Gaps created by delayed or mislaid letters added to the drama of the plot without seeming manipulative.

In Walker’s and Robinson’s novels the letters also offer a means to express intimate physical experience, sensibility and spirituality in a realist framework. They come straight from the heart without the scene setting and background provided in a more conventional narrative, even a modernist one. The letters in Walker’s novel become an emotional kaleidoscope of the experience of black women in the rural South. Ultimately, we must piece together the whole picture from the pieces and the gaps between them.

Gilead differs somewhat in being a single long letter documenting the life and family history of its writer, the Reverend John Ames. It is penned in 1956, giving it contextual plausibility. Addressed to his son, the letter focuses on Ames’ father and grandfather, selecting the details relevant for the boy to understand his origins and inheritance. Its confessional form makes the reader guess at the son’s character, wondering how he will receive his father’s words. Robinson said in interview that she composed the novel straight out in one burst, having holed up in a motel to write, as if Ames’ voice dictated it to her.

In the late 1990s I wrote an epistolary novel, Family Lines, letters between the women in a family, principally two sisters, with references to their mother and aunt. The novel sprang from a comment someone had made about the absence of studies of sisters, in a sociological or psychological sense. As I am a sister and have no brothers I decided to take up the challenge in fictional form. On an impulse I began to write it as a series of letters.

Looking back I realise that I enjoyed the freedom the form gave me to allow various characters speak straight from their own lives and to question one another without having to force that interrogation into a stilted dialogue. It remains unpublished and for a time I feared it would be anachronistic yet I could not convert the letters to emails because that would render the plot absurd. By now, I begin to fancy it could be acceptable as a historical novel, a story of its time. Watch this space . . .

Thank you for reading What’s the Story? If you enjoy it please pass on the word to your friends.

How do you feel about the letter vs the email? Are you a letter writer? Do share your thoughts on written communications and their merits, and the titles of your favourite epistolary novels.

I agree that the loss of the letter is going to reduce future generations' knowledge of the detail of people's lives. Only yesterday I heard on the radio a reference to letters between Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn about composition which casts an interesting light on his working method and her gifts as a composer, although she wasn't allowed to pursue that as a career. Maybe that's part of the value of letters - the hidden lives they can reveal. Possibly the journal can replace some of that - see this week's newsletter.

As for Family Lines, it was never published but I may serialise it here next year. The epistolary format lends itself to serialisation . . .

Thanks Vincent, glad you liked it! I hadn't heard of Yellowface but having looked it up I'm intrigued. Definitely on my TBR list!

Good point about Les Liaisons Dangereuses. That completely slipped my mind, perhaps because I haven't read it although there was a copy knocking around our house for a long time. However, I did see the play by Christopher Hampton and liked it - if that's the right word for such thoroughgoing cynicism. I see Netflix has made a modern version of the book . . . Insta instead of letters.

Thank you for filling that gap in my list. Another one TBR!