Writing on the Wall

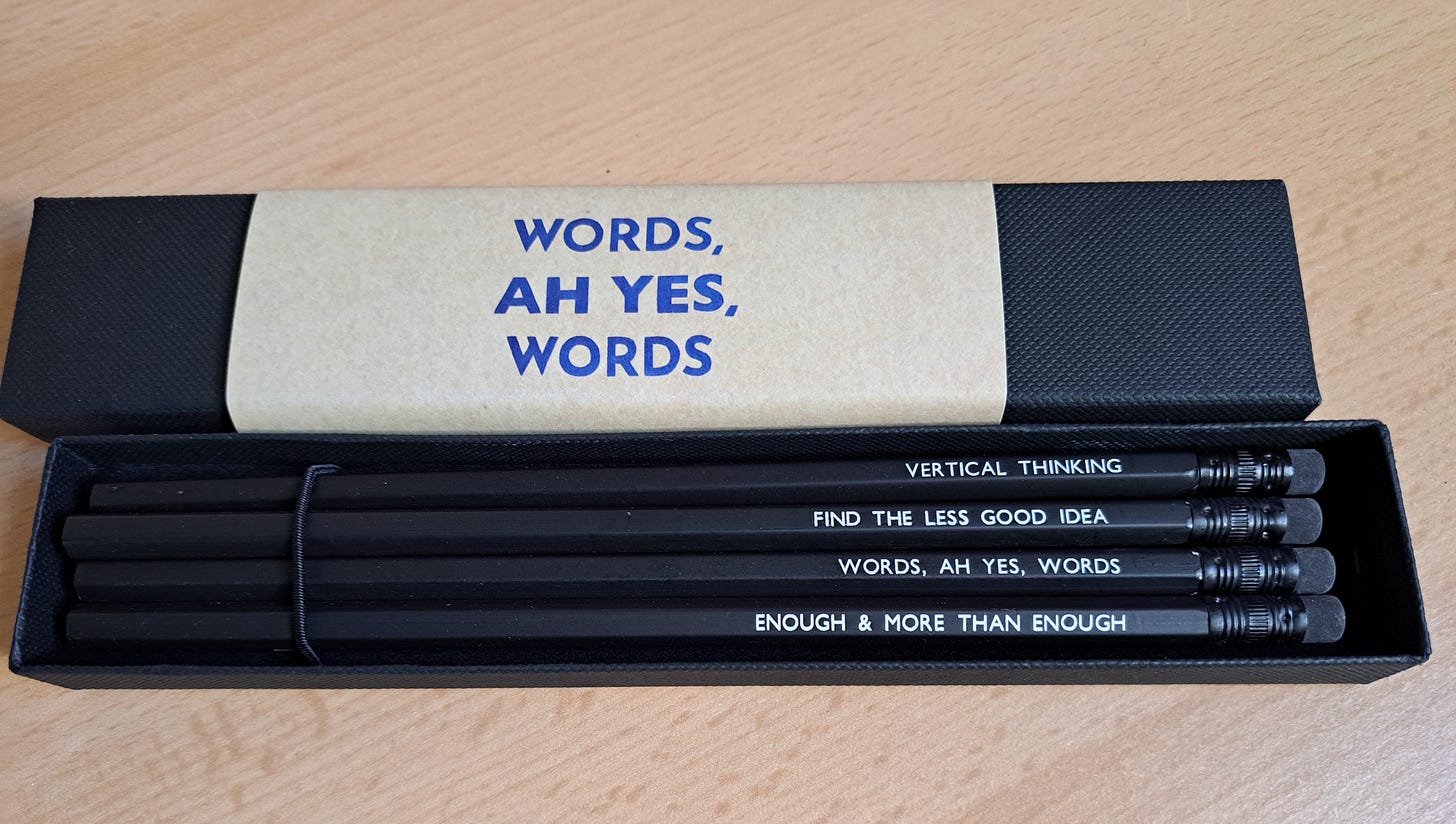

If the medium is the message how differently do we receive or perceive words presented as ‘visual’ art from those we read on the page or screen?

Take a walk through any neighbourhood and notice all the words you see, from advertising on hoardings and buses to business names on vans and lorries, from street and shop signs to graffiti and scraps of food wrappers, and on and on. The urban dwellers among us are surrounded by words to the point that half the time we scarcely notice them, and glance at familiar signage only to keep our bearings.

If you were to enter a shopping centre and see an LED sign above you saying PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT would you pause to wonder what it was selling? Context is all. Or is the medium the message, as Canadian philosopher, Marshall McLuhan (1911-80), claimed?

This ‘sign’ is a work by American conceptual artist Jenny Holzer (b.1950). One of her early works was ‘Truisms’ in which she printed the phrase quoted above, and others, including ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE, to distribute as flyers and paste on walls around New York. Now they are to be found on many surfaces such as mugs, condoms and tee-shirts, consistent with her aim to create art that is readily available to all.

Some may see this approach as sloganeering, others as a clever deployment of the texture of our daily lives to make us stop and think. The medium here is a combination of elements: the words, their typographical features (font, italic, roman, bold etc.), the page, LED display or mug on which they are printed, conditioning our response.

A subsequent work, ‘Inflammatory Essays’ is a series of 100 word ‘essays’ set in 20 lines, all caps, italicised and printed on coloured sheets of paper. When pasted onto a high gallery wall in vertical ribbons of colour they make a strong visual impact. The almost uniform blocks of print appear at first as a pattern on the coloured stripes. Up close we can read the ‘essays’ comprising terse phrases created by Holzer which are variously declamatory, celebratory and contradictory.

More recently she has used lines of poetry by Anna Świrszczyńska (Swir) (1909-84), Czesꝉaw Miꝉosz (1911-2004) and Wisꝉawa Szymborska (1923-2012), all of whom lived through the terrible events of Polish history in the twentieth century. Holzer has engraved their words in stone or marble, invoking endurance and monuments and has turned them into light displays. From Swir’s ‘Beauty Dies’ she extracts this fragment: ‘the beauty worshipped by generations of men/is burning’, and incises it into a red marble bench. The words are almost invisible in the striations of white and red stone but palpable.

If we can set poems to music why not sit them on a bench? Their effect, when we discover them, is to shake our composure as we rest in the middle of a gallery, and to wonder about the idea of beauty that galleries are said to house. [You can see her work here: Jenny Holzer]

By an associative leap carving poetry on stone suggests concrete poetry. In this form the poem is shaped like the object it describes, such as George Herbert’s (1593-1633) ‘Easter Wings’:

Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store,

Though foolishly he lost the same,

Decaying more and more,

Till he became

Most poore:

With thee

O let me rise

As larks, harmoniously,

And sing this day thy victories:

Then shall the fall further the flight in me.

My tender age in sorrow did beginne

And still with sicknesses and shame.

Thou didst so punish sinne,

That I became

Most thinne.

With thee

Let me combine,

And feel thy victorie:

For, if I imp my wing on thine,

Affliction shall advance the flight in me.

Or ‘A Bell is a Bearer of Time’ by Alison C. Rollins (b. 1987) which opens thus:

I am

a product

of my time.

Time is a body

that resembles

a sound without a scale.

Forever foreclosed fortitude.

. . .

Scottish writer, Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925-2006) took another tack, creating visual puns on words such as the names of boats, most beautifully in ‘Starlit Waters’ where the three-dimensional and uniformly upper case letters are carved in wood, painted green, set on a blue base and wrapped with orange fishing net. As a single item the netted words form the outline of a trawler but the netting also creates the illusion that the words are lilting as if at sea. (See the image here: Ian Hamilton Finlay) Like Holzer, Hamilton Finlay sometimes carved words on stone and even fashioned his garden, Stonypath/Little Sparta as a poem.

Where and how we see words conditions our interpretation of them. If we came across one of Holzer’s ‘Inflammatory Essays’ as a poster on the street or in a railway station we might wonder about the agenda of whoever placed it there. Were we to first find them bound in a book, with a preface or introduction, and author mugshot, we would read them through a more intimate lens, maybe flipping the pages back and forth to trace themes or recurring images.

On the street or public transport we are part of the mass, surrounded by messages that we only half read. Alone with our book, or electronic device, we digest and reflect slowly. Maybe Holzer has turned McLuhan on his head, delivering messages that prompt us to interrogate the media by which we are daily assailed.

Modern media allows the writer, however, to have it both ways, a public social media post can be read privately. The wall, physical and digital affords the protection of anonymity, should the artist, polemicist or coward choose that option. Who is Banksy?

The phrase ‘the writing’s on the wall’ derives from the story of Belshazzar’s feast in the biblical Book of Daniel, where a disembodied hand writes a dark prophecy on the king’s wall. Graffiti, on the other hand, has made its way into poetry, for example, in ‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’ by Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) where he writes ‘Is there a life before death? That’s chalked up/ In Ballymurphy’. By a curious twist, words of Heaney’s were in turn chalked up on walls around Ireland during the Covid pandemic, ‘If we winter this one out we can summer anywhere’.[1]

Richard Murphy’s (1927-2018) collection, The Mirror Wall (1989) is based on songs carved on the rock wall of an abandoned palace in Sri Lanka, between the eighth and tenth centuries. Mostly erotic, they are addressed to the images of women painted there in the fifth century.

This act of his in sewing up words he thought was making poetry. He sat down and wrote on the reflective wall plainly of things we could see. With no nectar in the sound no quicksilver at the core it can’t be poetry.

Being sign makers we seek symbols, patterns and meaning everywhere. The artist uses the materials to hand, including words, which in common coinage are rubbed and scuffed and sometimes hollowed out. The writer, the poet and the visual artist seek ways to burnish them anew and draw out as yet unyielded meanings.

[1] These words are taken from a 1972 interview with Heaney about the Troubles in Northern Ireland and may allude to lines from a song by W.F. Marshall (1888-1959) ‘I wunthered in wee Robert’s,/ I can summer anywhere.’

Thank you for joining me on What’s the Story? I’d love to hear your ideas on the question of conceptual art using words, writing on walls and elsewhere so please leave a comment here:

And don’t forget if you’re enjoying What’s the Story? share it with your friends! The more the merrier!

That's great Noirin!! Was that reverse advertising do you think or simply a statement of fact? And if it wasn't a shop what was it?

Thanks Vincent. Yes it's funny how we feel words speak to us even in, or maybe most of all in surprising places.