Friday reading

Will Marge's letter, filled with memories, explanations, and an apology, help Deb to understand her parents?

X MARGE

6 Harold’s Cross Cottages

Dublin 6

3 May 1996

Dearest Deborah

I have read your long letter and its enclosures twice, first with a mounting sense of frustration and again, next day, with a mixture of regret and relief. Regret for all the pain that might have been spared to you and your family if the truth had been revealed sooner and relief that at last you know all there is to know about your birth. I feel keenly how utterly devastating these revelations must be for you. Perhaps I owe you an apology, many apologies, but first I wish I could give you a big hug, just like the ones we shared when you and Lucy were toddlers. I can still feel the pressure of your busy little limbs in my arms, the softness of your hair against my cheek and the fragrance of Lux flakes from your clothes.

Do you remember those Sunday afternoons? No sooner was I seated on the sofa than Lucy squinched in beside me, babbling wildly about her latest adventure (usually imaginary) while you sat upright, my handbag on your lap, preparing to rummage through its contents, and not only in hope of finding sweets there. Every item had to be taken out and examined, the lipstick tested, the compact flipped for you to admire yourself, the cigarettes inhaled (I took the precaution of putting the matches in my pocket where you couldn’t get at them), the change purse opened and the money counted, the pocket diary leafed through. Sometimes, while I was distracted, you made a small drawing on one of the blank pages, which I found weeks later on going to note an appointment for the date you had picked at random. They always made me smile.

Oh dear, there I go again, wandering off the point. To be honest, I am avoiding it. There again, I’m at a loss as to how to begin to tell you what I know, what I knew, and what I failed to do. Mea culpa. I do not expect absolution from you. You would be well within your rights to berate me and cut off all contact with me, again, but this time for good. My pupils would derive malicious amusement from my hesitation. “Miss,” they would say, “you need a beginning, a middle and an end, in that order: introduction, development and conclusion.” They would be right. How many times have I taken the red pen to their slapdash work, reminded them to write a plan before committing themselves to the composition, or drawn a line through their lazy plagiarism? I will be kinder to them in future. I promise. Myself, I deserve no kindness.

In line with my own classroom advice I will begin at the beginning, which, for me, is the moment Denis met Dolores and set in chain the consequences we are living out now. He had come to live with me in Dublin in 1973, having been dismissed from the family farm by our eldest brother, Eddie, sole heir to the house and land.

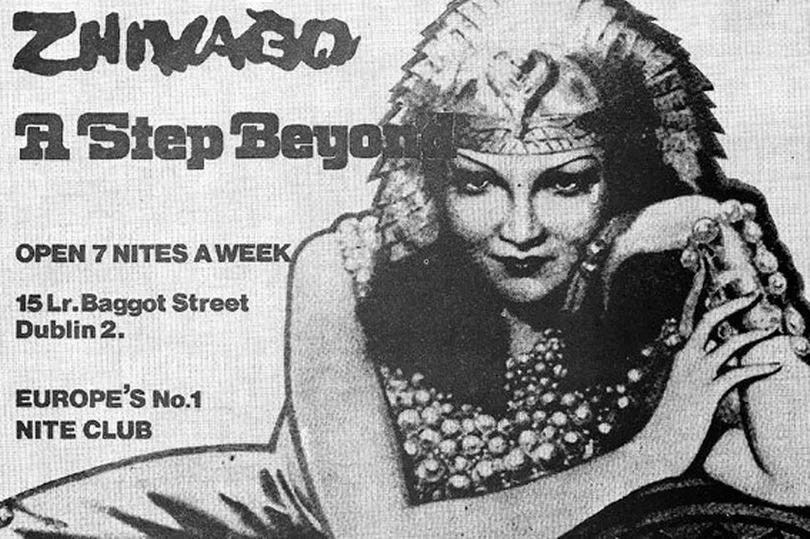

Denis was five years younger than me and at a loss what to do with his life because he had loved the farming. He shilly-shallied about joining one brother in America or another in Australia. While he tried to make up his mind he took on various part-time jobs until he landed a full-time position with Homebright Paints. To celebrate his first wage packet he went with a pal to Zhivago’s night club, and there he met Dolores. The club’s advertisement said “Where Love Stories Begin” and that proved true for them.

He was in a swither of excitement the next day telling me he had met a smashing girl who had agreed to meet him again. They walked out together for a while before he introduced her to me. She had told him about you on their first date, saying if he had a problem with the arrangement he could walk away there and then. Where she went you went. Betty had already gone away and nobody knew when or whether she would be back. I was a little apprehensive on that score, wondering if she was luring him into a trap to provide for the two of you. As you know Denis is a softie and might have been easily persuaded, even flattered by Dolores’ attentions.

When I met her my reservations dissipated. Yes, she was four years older than Denis, closer in age to me than to him, and more worldly wise than he. Nevertheless, I warmed to her because she was open and funny, and she held you in her arms. How could I not love the two of you? At first your face puckered in a little frown and you turned away to bury your head in her chest.

A few minutes later she set you on the floor and asked me for a saucepan and a wooden spoon. Soon you were banging the makeshift drum, laughing and looking at me with a confident happy smile. I watched the three of you leave, Denis steering your push-chair, Dolores linking his arm, you waving your arms and legs, and I knew they would marry. That happened a little sooner than they might have planned because Dolores discovered Lucy was on the way. Lucy does not know that.

No doubt you are wondering why if I knew all these secrets they could not have been shared with you and Lucy, whom they touch more nearly. It is a valid question but maybe you need to understand the mood of the times. Back then the notion of extra-marital sex was taboo, a sin to be punished, and therefore children born ‘out of wedlock’ carried the stain of their parents’ sin. Being married made everything all right. It smoothed over the surface, no questions asked. When you reached twelve or thirteen, however, I advised Dolores to tell you the truth about yourself. She recoiled from the suggestion as if I had scalded her.

Denis backed her up, even though, privately, he shared his doubts with me. Dolores was adamant, refusing to countenance my concern about your hearing it from someone else, and he would not cross her. Instead, he bowed to her insistence that she knew best what was best for you. He had seen enough trouble in our large warring family to want to turn away from any suggestion of conflict in his own. Dolores took moral refuge in the claim of a mother’s instinct being infallible. How she lived to rue her obstinacy. Like Denis, I had no relish for a family dispute and it would have ill behoved me to be the cause of a row between him and her so, with misgivings, I let the matter drop. After all, you were, to all practical and emotional intents and purposes, her daughter and I had no right to interfere in her bond with you.

I mentioned the subject once again, when you were doing your family tree project, which struck me as the perfect moment to untangle all the crossed lines of your background, for once and for all, for good or ill. Still Dolores refused. Her greatest fear, you see, was of your going in search of your birth parents. When poor Betty passed away she still dreaded your looking for Jim. In her book he was bad news, to be avoided at whatever cost. Reading between the lines of your and Ellen’s letters I have a sense of him being more irresponsible or misguided than bad. He is very fortunate to have met Ellen who loves him unconditionally, and whose wisdom helps to keep his feet on the ground.

Dolores had told me he could be very charming, if dishonest. Hence her fear of his potential to woo you away from her. If Dolores had a fault it was loving you too much. You had become a tight unit in the first year of your life when she, and your Nanna, did all in their power to protect you and compensate for Betty’s depression and Jim’s betrayal. Your Nanna’s experience of betrayal by your seafaring grandfather had prepared her well for taking you into her care.

Dolores never mentioned her conversation with you about Jim until after you were gone. I asked had she told you about Betty but she only shook her head and said, “So after all, I was a bad mother too.” I held her hand, offering reassurances about how wonderful a mother she had been, reminding her how many others in your Nanna’s place, and hers, would have either pushed Betty to go away to England to have her baby out of sight, or shut her into a convent and insist she give you up for adoption. Over and over, I said she had never wavered from loving you and could not take responsibility for whatever had befallen you. The look on her face of bewilderment and grief, mixed with horror, frightened me as she said, “But you told me to tell her and I didn’t. I didn’t. I was selfish. I wanted her all to myself.”

There were many afternoons we sat so at your kitchen table, her crying, me trying to console her, the tap dripping, the clock on the window sill ticking, waiting. We were on edge all those years, our minds tuned to receive the slightest hint of news of you. The silences we lapsed into became a habit, a hovering stillness and while we held our breath our minds ran over all the things we could have said, should have said or done, trying to second guess your reasons for leaving if indeed you had left, and not been taken. In all that pondering and surmise the one possibility we never considered was whether you had fled someone else. Your assailant, the loathsome Mr. Johnston, never entered our thinking.

I allowed myself a tiny smile at your question about my single status, or spinsterhood as it would have been termed not so long ago. I understand why you asked. It is a reflection of your own surprise at finding yourself in a lesbian relationship. In answer to your question, no, I am not a lesbian. I had men friends in the past, one I was very keen on but I turned him down because I did not want to compromise myself or my independence. Strange to say, I met him recently at the theatre, with his wife. The friend I was with laughed afterwards at how like me she was. I didn’t see the resemblance but I wouldn’t would I? I felt no regret at my decision, pleasant as he was.

Dolores was like a sister to me, in place of those who had gone overseas or fallen out with the rest of our family. She and I formed a strong alliance partly born of the shared knowledge of your birth. Later, when Denis had his financial troubles she confided her concerns to me. She was very afraid for him at one stage when he was sunk. He felt he had failed her and you and Lucy. Your departure wounded him to his core. He took it personally, seeing the day you did not come home as an omen of further decline. Superstitious as such a notion sounds, his determination to succeed in his scheme weakened when you were gone. The heart was gone out of it, out of us all. There were days when our grief for you undermined our will to keep on going. Only the possibility that you would return helped pull us out of ourselves.

You may wonder why, if I knew your story and thought you should know it too, I did not tell you myself. I hope you understand I could not betray my brother and my close friend and maybe set them at loggerheads, and so cause suffering for you and Lucy. I knew my place was on the periphery of your lives, not as a voyeur, more like a guardian angel, watching over and protecting you all. I had no way of knowing how you might have reacted to such news and certainly did not want to provoke any anger, shame or rage, which you would surely have taken out on Dolores, maybe on Denis too. I loved you all too much to inflict such pain. Maybe I was wrong.

In conclusion (my pupils would be proud of me!) I have to tell you that I passed on the entire bundle of letters to Lucy. She asked me what was in them and why you had written to me and not to her. “The truth,” I said. “Not more of it,” she heaved a great sigh. I nodded and told her to telephone me when she had read the letters. Shay was there at the time and shot me a concerned look over her head, which I met with a concerned expression of my own.

In case I do not hear from you again Deb, let me sign off by saying I regret utterly the silences and secrets which have affected you so deeply. I also regret your own silence about what was done to you. We must take some responsibility for not showing you how to be open with us. I am sorry, deeply sorry, for you and for all of us. I too failed you. Forgive me.

Your ever loving

Auntie Marge

Thank you as ever for reading Family Lines so attentively. I really appreciate the care you take in commenting on the story. And I'm very sorry you felt let down by this chapter. Marge's phrase 'birth parents' is used because she knows now that Deb knows the truth of her parentage. See Ellen's letter at the end of the preceding chapter. By now there are no more secrets. But I can see it is a somewhat impersonal phrase for her to use in the context.

Betty was younger and more naive than Dolores. But Jim had only had a fling with Betty. In a previous draft I had referred to him having 'a fling with a yellow dress'. Dolores was the one he was serious about.

As for her pregnancy being managed by her mother and sister, this was a more benign solution than the ones Marge mentions in her letter, which after all were the traditional ones at that time in Ireland. Betty wasn't in a position to keep a child, especially after Jim's departure. But of course you're right she might not have been entirely happy about being taken over by others.

I plan to read through the whole manuscript now that I have completed it and will iron out any inconsistencies at that stage. So thank you for pointing out the weak spots. Your help will make me a better writer!

Thank you. I guess the truth is hard to bear no matter when one hears it. I'm happy that the story continues to captivate you.